Vimyism is alive and well in post-Harper Canada

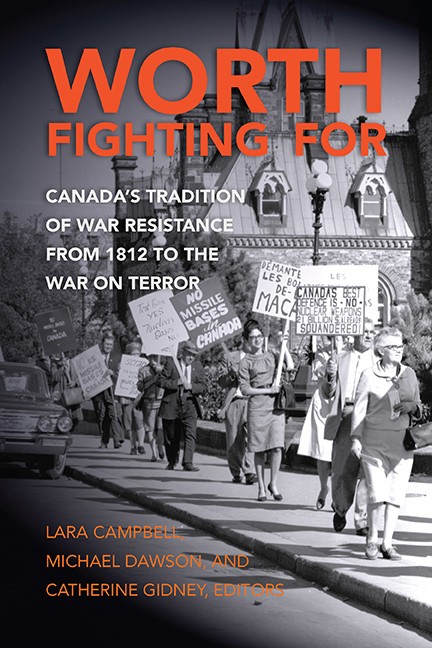

From the first Armistice Day in 1921, which became Remembrance Day, there has always been an emphasis on soldier-heroes and the dignity of arms. But patriotic emotionalism has not always dominated.

That’s because war memory is contested terrain. Canada’s longest serving prime minister, William Lyon Mackenzie King, cared deeply about the memory of the Great War that ended on November 11, 1918. Indeed, during the fevered patriotic lead-up to that horrific disaster, well before he became prime minister, he complained about those who spoke of “our” Empire and denounced martial nationalists he called “the Jingoes” for stirring things up.

By 1936, King was well ensconced as prime minister, and Canada’s most famous war memorial at Vimy Ridge had been unveiled. Walter Allward’s splendid monument on France’s Douai Plain is a site of mourning, essentially a peace monument lacking any whiff of patriotism or militarism. Indeed, one of Allward’s prominent Vimy Ridge statues depicts the breaking of a sword, a clear reflection of the biblical injunction—beating swords into ploughshares, the weapons of war into the tools of peace. Allward called his masterwork “a sermon in stone against the futility of war.”

The prime minister’s official Armistice Day address later that year began with brief mentions of the war dead and the calamity of war, before a lengthy exploration of the need to preserve peace.

By the early twenty-first century and the onset of Stephen Harper’s martial nationalism, things had taken a decidedly bellicose and patriotic turn when it came to Remembrance Day. Highway 401 in Ontario had been rebranded the “Highway of Heroes.” An elaborate work by Haida sculptor Bill Reid featured on every $20 bill was replaced by an image of the Vimy Memorial flanked by red poppies. Canada’s ill-fated counterinsurgency in Afghanistan was at its peak.

In 2016, historian Ian McKay and I coined the term “Vimyism” to describe a network of ideas and symbols that treat Canada’s Great War experience as the official story -- a national creation story -- while sanctifying militarism and war. We hoped our book, The Vimy Trap, would offer a counterweight to Canada’s official story by explaining Remembrance Day’s complex history.

On Nov. 11, 2008, I attended a Remembrance Day ceremony in Kingston, just as Canada’s disastrous war in Kandahar was raging. Uniformed men fired guns into the air. A retired colonel told the crowd that soldiers, not writers, had given Canada press freedom. Pointing a white-gloved hand towards nearby Queen’s University, this patriot made the puzzling claim that “It has been soldiers, not campus agitators, who have given us the right to protest.” A breathless local deejay told people to remember the troops in Afghanistan. “Remember that if they weren’t there, we wouldn’t be here.”

As if the military ever had had anything whatsoever to do with civil liberties and freedom. Vimyism writ large.

Literary critic Sherrill Grace has explained that “history is like a field of hiding stones/stories that continue to surface and, as they surface, change the story, alter the landscape, make room for new, for more, stories and allow us to see/hear the repressed, forgotten memories excised from the official story of Canada and its wars.”

How will September 30, the new National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, stack up against November 11? Will a mass of orange ribbons ever match the Legion’s now-ubiquitous red poppies, which have seemingly become compulsory for politicians and television presenters? Will solemn, state-sanctioned September 30 ceremonies marking Canada’s genocide become a widely observed Canadian occasion?

It is too early to tell. But this year the prime minister chose to take a beach holiday, passing on an invitation from the Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation to join in a Kamloops Residential School remembrance event.

He generally attends Remembrance Day ceremonies, along with events like the 2016 unveiling of a memorial at CFB Borden. “The reason the world pays heed to Canada,” Trudeau proclaimed, “is because we fought like lions in the trenches of World War I, on the beaches of World War II, and in theatres and conflicts scattered around the globe.”

It seems that Prime Minister Trudeau is keen on keeping Vimyism alive in post-Harper Canada.