Music, Film, and Political Deadlock in Cuba

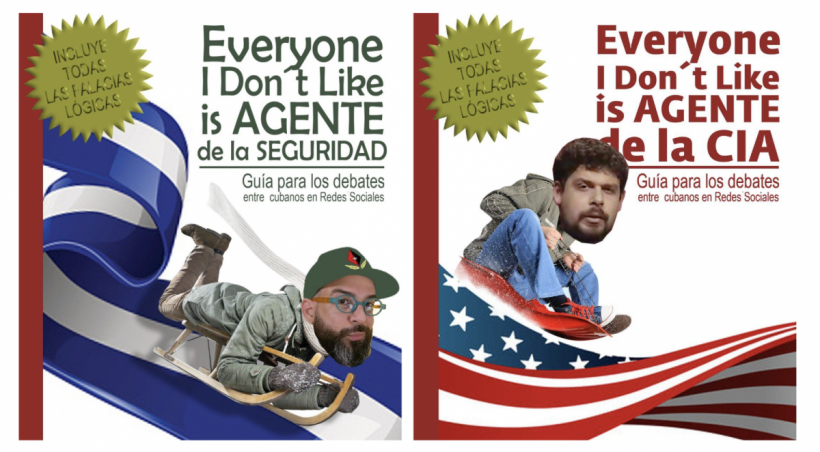

Making fun of polarization: left image - “Everyone I don’t like is a State Security Agent - A Guide for debates among Cubans on social media” (Cuban American personality in Miami); right image - “Everyone I don’t like is a CIA Agent - A Guide for debates among Cubans on social media” (Cuban state TV personality)

On a recent Saturday in Havana, I was thrilled to learn that Interactivo was performing an outdoor concert. A jazz fusion band that recently celebrated its twentieth anniversary, Interactivo had a regular weekly gig in the basement bar at Brecht Theatre in Vedado for years, a venue they recently lost. Another concert scheduled for the huge Chaplin Theatre in October was also cancelled, which was why I was so happy to learn of this outdoor concert, to take place in a park across the street from their usual Brecht location, during the opening weekend of the Festival Internacional del Nuevo Cine Latinoamericano, an annual event that often brings me to the country.

But it was not to be. A couple of hours before the concert, bandleader Roberto Carcasses announced on social media that this gig too was cancelled. “Bad weather” was the reason given by the authorities. There was indeed some wind, but no rain. I could not help but wonder if this spate of cancellations Interactivo has run into have something to do with Roberto Carcasses’ outspoken defence of freedom of expression and against the severe prison sentences handed out to those convicted of various forms of “sedition” in the protests of July 2021 throughout the island. Interactivo is known for its musicianship and high-octane performances. Their lyrics do not, typically, generate controversy. Yet Carcasses himself takes risks. He is known to sing (and speak) tributes to open-heartedness over ideology. A recent song, written on the occasion of the 2021 protests by artists outside the Ministry of Culture, proclaims his love for his “Trumpista” uncle in Miami as much as his “Fidelista” aunt in Havana.

So instead of seeing my beloved Interactivo, I made my way to Chaplin Theatre to see the premiere of Fernando Pérez’ new film El Mundo de Nelsito (Nelson’s World). This was hardly a bad second choice. Like Carcasses, Perez is also a beloved figure in Cuban culture. His films depict the city of Havana as a curator might in the world’s best gallery, and the city loves him back. El Mundo de Nelsito continues his tradition of profoundly human filmmaking and was clearly loved at its premiere: the first and only full theatre I saw during the festival (films are almost always sold out at this event). I think the audience was captured as much by Pérez’ introduction as by the film itself. Visiting his family outside the country, he spoke by video. He warned the audience that the film was a jigsaw puzzle and asked us to give it time to come together (he was correct, and we did, and it was worth it). He also addressed Cuba’s current moment directly: “I dream of a country where films are not censored,” he said, referring perhaps to Carlos Lechuga’s 2022 release, Vicenta B, a meditation on migration and family separation, featuring Afro-Cuban protagonists, a film that was famously and scandalously excluded from this festival. “I dream of a country where protest is not criminalized,” Pérez’ also said, a reference, perhaps, to a state that, in the name of revolution, jails teenage protestors.

Pérez was not the only one to speak up at this festival. At the festival’s opening ceremonies, actress Andrea Doimeadios took the stage. Referring to herself as “the only young actress who wants to be in Cuba right now,” she proceeded to poke fun at some of the assembled functionaries. Addressing the head of the Department of “Ideologico del Partido de PCC,” she said, “I’ve always wondered what you all talk about in that department.” She comes by her sarcasm honestly: she’s the daughter of a celebrated humourist. A couple days later the head of the major film school on the island denounced the country’s filmmakers for being “anti-communist.” In return, a letter of thanks to the festival was circulated by a number of filmmakers, actors, and other participants. Cuba is a country that, in addition to enduring the plethora of long-time sanctions applied by the US (and continued by Biden), has still not recovered from a devastating hurricane that took out the entire electrical supply in September. Some areas outside Havana are still experiencing blackouts of eight to ten hours daily. The economy continues in freefall, and inflation is crippling access to basic foods (as well as much else). Food prices have tripled, at least, in the past year. The example repeated to me by several friends was: a dozen eggs cost over 1,000 Cuban pesos (beyond the 5 eggs per person monthly quota provided by the state). The average wage is around 4,000 per month; pensioners receive 2,000 monthly. Roughly translated, in terms of an average Canadian salary, an “extra” dozen eggs would cost almost $500. Problems this severe often lead to one solution: getting out. The country continues to experience high rates of outmigration: approximately 250,000 this year, more than the number of migrants in other well-known crisis periods in the past decades.

With problems such as these, who cares what artists say? Actually, the answer is plenty of people, given the importance of the arts and culture in Cuban history. Artistic education and access to the arts has been one of the hallmarks of Cuban state policy for decades. When popular jazz singer Daymé Arocena (who lived at the time in Canada) recorded a song and video in support of the July 2021 protests, none other than the Minister of Culture himself went after her, trashing the work as “insignificant” artistically. When political leaders go after insignificant musicians (with a huge domestic and international following), the place of music in this climate of political tensions is clear.

The film festival was just one example of the political polarization and mistrust that characterizes Cuba today, in the cultural world, on social media, and amidst the continued economic crises and inequalities that helped to create the climate of unprecedented public protests. There are Cubans abroad who advocate for the cessation of remittances to families on the island, in order to increase pressure for regime change. This strategy of “starve your grandma to bring down the government” is yet another indication of the high-stakes fault lines. As one friend said to me (herself an Afro-Cuban woman in the cultural world, located well outside the privileges of state power), the ugliness of this climate is even sadder when set next to the spirit of neighbourly cooperation that characterized the pandemic and quarantine period in Cuba - not to mention the success in developing a vaccine independently and distributing it throughout the island.

This context is useful to explain why the increasingly restricted space (literally and metaphorically) for films and music is profoundly connected to current economic and political crises. Musicians and other artists of course find themselves among the current wave of migrants. Oliver Valdes, a popular drummer, now performs occasionally with a group of musicians he calls Los que se Quedaron: ‘those who stayed’ - satirical Cuban humour at its best. I would have had more opportunities to hear some of my favourite Cuban musicians in Miami than I did in Havana. And one hardly even needs to leave Canada to hear first-class Cuban musicians. A new generation of Cuban migrants are making a name for themselves here: Elizabeth Rodríguez and Magdelys Savigne of the Juno winning OKAN, jazz saxophonist Luis Deniz. Newly-emigrated musicians are taking their place alongside celebrated Cuban musicians who have been in Canada for decades: Alex Cuba, Alexis Baro, and Hilario Duran, just to mention a few examples. More to the point, unless the open-minded and open-hearted embrace of a multiplicity of perspectives advocated by the many artists like Carcasses and Pérez prevails, this climate of polarization will continue, to everyone’s detriment.