Credit Where Credit Is Due: Financial Literacy and the New Ontario Mathematics Curriculum

I never thought I’d say it, but the Ford government has finally figured it out. A new mathematics curriculum guide is set to drop this September, the first update since 2005. Not only will students be heading back to the basics, but they’ll also be introduced to a new ‘strand’ of learning: financial literacy.

The reason I’m so excited about this development is that at the very heart of teaching mathematics for social justice is the understanding that we are all inextricably linked to each other through economic relationships. There can be nothing more basic than learning to tease apart these relationships to demonstrate that people’s political, economic, and social experiences hinge on a complex tapestry of financial policies and interactions.

In the mathematics classroom, if we can make these interactions visible, we set the stage not only for rich, complex mathematics skill development, but also for direct action to make the world a better place.

If you’re new to teaching mathematics for social justice, a seasoned pro, or somewhere along the journey, I’ve pulled together a few possible directions for the upcoming financial literacy expectations.

Identify and describe reliable sources of information that can help with planning for a financial goal

The Fraser Institute is a Canadian think tank with a great motto: If It Matters, We Measure It. But here’s the thing. Measurement is inevitably a political process: we come to different conclusions depending on if and what we choose to measure and how we choose to measure it. The Fraser Institute is considered a conservative, libertarian organization and so it would fit nicely in a critical mathematics classroom when looking at the financial implications of their reports and recommendations.

When looking for ‘reliable’ sources of information, teaching students to expose an organization’s funding sources can put the conclusions they come to into perspective. If, for example, the Fraser Institute accepts hundreds of thousands of dollars from the business community, we could ask whether their financial advice happens to benefit… the business community and the wealthy elite.

If we’re looking for a different perspective though, we might look at the Canadian Centre For Policy Alternative’s Alternative Federal Budget. Here is how the CCPA describes this project:

“The Alternative Federal Budget is a 'what if' exercise—what a government could do if it were truly committed to an economic, social, and environmental agenda that reflects the values of the large majority of Canadians—as opposed to the interests of a privileged minority. It demonstrates in a concrete and compelling way that another world really is possible.”

As we plan for more fair and just communities, especially throughout and in the wake of Covid-19, reliable sources of information will be a cornerstone, especially when it comes to understanding the financials behind our goal setting.

Create, track and adjust sample budgets designed to meet longer-term financial goals

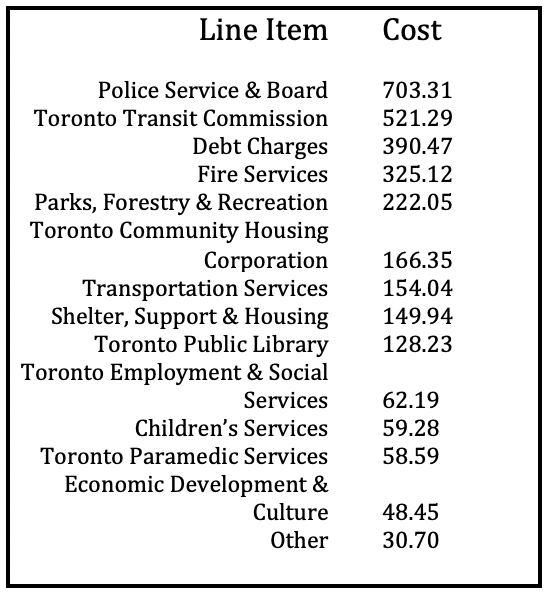

One source of inspiration that students can use when making their own budget is their city budget. In Toronto, as elsewhere, property taxes fuel municipal services, and taking a close look at where and in what proportions that money is spent is central to any fight for social justice.

The following breakdown of a property tax bill is based on a homeowner who is paying $3,020 a year:

Each line item in the city budget is the result of priority setting and decision-making. As you can see, one particular cost sticks out above all others, and it’s not library services. Given the widespread and well past-due attention on anti-Black racism, we can turn to a recent motion from two city counselors to defund the police by reducing their budget by 10% (or about 122 million dollars). The idea was to divert those dollars to funding other underfunded services that would support our communities in ways that don’t require firearms and use of lethal force. Imagine $122 million dollars a year to provide high quality youth programming, subsidized housing or better employment services!!

But why 10%? Why not 50%, as Black Lives Matter Toronto has suggested? Or as abolitionists have argued, a complete revamping of police services altogether? Students working together to design their own city budget can engage in rich conversations, thinking outside of the box about how financial decisions impact the health of their communities.

Identify various societal and personal factors that may influence financial decision making

Fast food workers in New York had finally had enough. In 2012, two hundred of them walked off of the job, sparking a six-continent, 300-city fight for a $15 minimum wage. My students are likely to enter the workforce earning this amount or less, so it seems like a particularly important discussion.

Using the basic algebraic equation y = 15x, students can create a t-chart of values for total pay (y) versus hours worked (x). They can then plot those points on a graph to see the pattern. With some research, we can explore the difference between a minimum wage and a living wage, and plot the new pattern on their graph. Spoiler alert: it will have a steeper slope.

Students can also discover the difference between unionized and non-unionized hourly wages and plot them. And, as they begin to plan for a place of their own, they can solve for the number of hours of work it will take at all of the above rates to pay for their monthly rent. Or, thinking long term, how a college or university education will be financed.

Dozens of questions follow. Can employers be exempted from paying minimum wage? Under which circumstances? Which governments have blocked minimum wage increases and under which pretenses? When minimum wage is increased, does it have an impact on everyone equally, or do some communities benefit more? Are minimum wage earners predominantly young people? How are Ontario’s migrant workers compensated? What about gig workers? What other ways are there to address systemic poverty beyond adjusting the minimum wage?

Explain how interest rates can impact savings, investments, and the cost of borrowing to pay for goods and services over time

Interest rates. They sound so boring. I find them fascinating. In my latest book, the lesson “Shark Infested Waters” explores the concept of annual percentage rate, or APR. It’s the cost of taking out a loan, and what’s important is that if you don’t have access to a low interest line of credit from a bank, other service providers will happily step in to fill the need. They are called payday loan centres.

While the APR on a bank loan can be as low as 3, taking a payday loan in Ontario can have an APR of 548, and in Nova Scotia, over 800. Not withstanding the law, which caps annual interest at 60%, sneakily added fees push the effective APR to dizzying heights. There are two million Canadians a year who depend on payday loan centres, feeding a two billion dollar a year industry.

Students can also explore the concept of correlation, asking if the location of payday loan centres tend to appear in certain locations and not others. Of course there are numerous other forms of high interest loans, and they can be compared and contrasted. And solutions have been proposed: what, for example, is the postal banking campaign and how does it address predatory payday loan centres?

There are other things beyond interest rates that impact savings. For example, the corporate tax rate has an impact on how many dollars from the corporate world are returned to governments, in order to pay for services that we hold dear. As the Panama Papers made abundantly clear in 2016, money can be easily hidden in offshore tax havens: 900 Canadian individuals and corporations were identified minimizing their tax returns. With close to 200 billion dollars sitting in the top tax havens around the world, the Canadian government ends up with about 8 billion fewer dollars per year. Students could develop a plan for how to use that missing money, in the event that our government grew a conscience and closed tax loopholes.

Financial Literacy: Bring It On

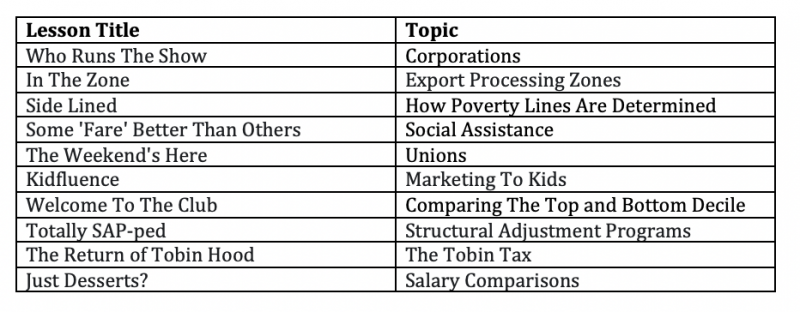

In 2005, I wrote a book called Maththatmatters, a collection of 50 lessons linking mathematics and social justice. It was published by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, who in June 2020 made the resource freely available at https://www.policyalternatives.ca/publications/reports/math-matters-2. Looking back, these are the lessons that might fit well in a classroom talking about financial literacy:

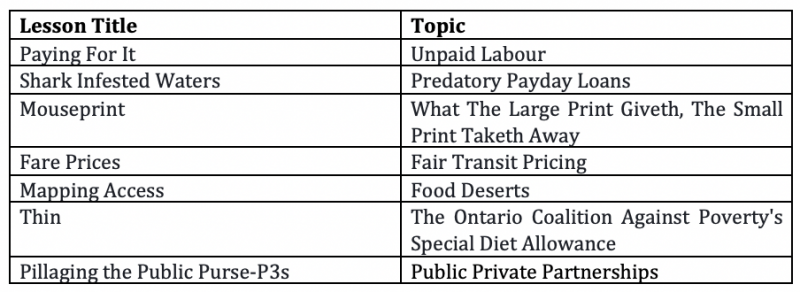

More recently, Maththatmatters 2 was published with a new 50 lessons. Again, there are many options to work with to teach financial literacy. Here are a few of them:

In the government’s press release about the new math curriculum, they write, “Educators will…continue to benefit from investments in professional development and math supports, including $10 million for board-based math learning leads, $15 million for school-based math learning facilitators, and $15 million to support release time for educators to become expertly familiar with the curriculum.”

Folx, let’s give credit where credit is due. This focus on financial literacy is visionary. Bravo, Conservatives. Just let me know when I can begin running professional development workshops.